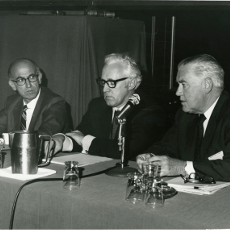

Dr. Jonas Salk, Dr. Frank T. Perkins, and Dr. Roderick Murray

Dr. Jonas Salk, Dr. Frank T. Perkins, and Dr. Roderick Murray

As we celebrate our 75th anniversary, we’ve rediscovered some interesting tidbits about the activities of our past Annual Scientific Meetings. Did you know our annual fundraising event, started by Joseph A. Bellanti, MD, FACAAI, former College historian and past president, began in 1991 featuring Tony Bennett as the College celebrated its 50th anniversary in New York City? The funds from the event were designated to support asthma camps and the College’s nascent Scholars Program. It was a huge success and laid the foundation for fund raising events throughout the years. Since then, College members have partied with everyone from the Beach Boys to Willie Nelson during these events. Or did you catch our article on the only College international meeting, held in Paris? Our annual programs have featured internationally renowned experts in the fields of allergy and immunology. In 1958, Bela Schick hosted a luncheon to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the field of allergy by Clemens von Pirquet. Barbara Bush was an invited speaker at the 1995 annual meeting where she charmed attendees with her remembrances as First Lady while championing her dedication to the Literacy Program.

Our Annual Meeting in 1971, in San Francisco, was no exception. In addition to featured speaker Abigail van Buren (of “Dear Abby” fame), Jonas Salk, MD, credited with the discovery of, the first inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), presented, “Is There a Need for Immunologic Adjuvants? Others speaking with Dr. Salk were Frank Perkins, BFc, MSc, PhD, head of the Division of Immunological Products Control at the National Institute for Medical Research in London, and Roderick Murray, MD, from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Perkins presented “Experience in the Use of Oil Adjuvants in Influenza Vaccine in the United Kingdom” and Dr. Murray spoke on “Studies of Oil Adjuvants by the Division of Biologic Standards”.

For some of us, it can be hard to imagine what it was like during the peak polio outbreaks in the 1940s and 1950s. Swimming pools were closed and activities involving large numbers of people, e.g., theaters and dances were limited. The tank respirator, better known as ‘the iron lung’, was used to sustain patients unable to breathe on their own. Thanks to Dr. Salk and Albert B. Sabin, MD, creator of the oral polio vaccine (OPV), the disease is all but eliminated in most countries. But the paralysis, death and fear the disease provoked were very real. President Franklin D. Roosevelt suffered from paralysis from polio, and passed away before the vaccines were developed. Together with his attorney friend and advisor Basil F. O’Connor, President Roosevelt created the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP – later named the March of Dimes Foundation). The NFIP’s mission was to make sure people with polio were assisted and that scientists had funding for research.

Both Drs. Salk and Sabin conducted their vaccine research with funds from the NFIP. After testing the vaccine on thousands of monkeys, both investigators moved on to human trials. Dr. Salk injected himself, his wife and three sons in his kitchen, as well as children at two Pittsburgh-area institutions with his IPV. Sabin also tested his OPV strains on humans, including himself and his family, research associates, and prisoners. By 1955, the IPV vaccine was officially declared “safe, effective and potent.” And the first clinical trials of the IPV were commenced by Dr. Salk.

Unfortunately, in April 1955, as the IPV vaccine started to become available to eager parents and children, a problem arose. Cutter Laboratories, one of three companies producing the vaccine, had to recall all their vaccines. Live poliovirus was present in some of the vaccine lots. Of the 400,000 people, primarily grade-school children, inoculated with the Cutter vaccine, about 40,000 children developed abortive polio (a short-lived, mild form of the disease) and around 260 contracted full-blown polio (close to 200 involving paralysis), resulting in 10 deaths. According to Dr. Bellanti, it was “one of the greatest disasters in the history of vaccine development.”

While many considered Dr. Salk’s vaccine ‘risky,’ it wasn’t the IPV itself that caused the problem. The virus in his vaccine needed to be inactivated with formaldehyde. At Cutter Laboratories, the viral inactivation protocol was not followed closely, and all the strict safeguards in place during field testing were not required for commercial production. An insufficient amount of formaldehyde was used, and the virus was not effectively killed.

As a response to what is known as the Cutter Incident, the Division of Biologics Standards was created at the NIH – now known as the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and the Center for Biologics and Evaluation Research – both part of the Food and Drug Administration. But in 1955, it was still part of the NIH – and led by the same Dr. Murray who spoke with Drs. Salk and Perkins at our 1971 College meeting. A major scope of Dr. Murray’s activities was to provide guidance for greater vaccine surveillance to prevent anything similar from happening again.

In the race to develop a safe and effective polio vaccine during this tumultuous period, Dr. Sabin continued his live-virus vaccine research. Like many researchers of the day, Sabin strongly disagreed with Salk’s approach of using injected, “killed” virus. He believed long-term immunity could only be achieved with a live, weakened virus, which was more easily administered orally. This virus could induce protective immunity in both the serum and the gut (the Salk vaccine induced only serum antibody) and could create “herd immunity” by spreading to others. The Sabin OPV was licensed in 1961 and was used in general routine immunization in the US until 2000. Then, because of vaccine-associated paralytic polio, in vaccine recipients or their contacts, IPV replaced OPV for the routine prevention of polio. But OPV is still used by the World Health Organization (WHO) on a worldwide basis because of its ease of administration and effectiveness.

And, in case you were wondering – Dr. Perkins was involved with Dr. Salk and the Cutter Incident as well. Dr. Salk wanted to re-introduce his inactivated vaccine, which, post-incident, had been largely replaced by Dr. Sabin’s OPV. Dr. Perkins was collaborating with the WHO and was responsible for quality control of vaccines worldwide. He advised Dr. Salk to connect with Charles Meriux, who could help him produce the vaccine safely on an industrial scale. It was good advice – Dr. Salk’s vaccine was re-introduced at the end of the 1980s, and is the one currently used today in the U.S.

Looking back on the Cutter Incident, it’s easy to label it a complete and total disaster. Though Dr. Sabin’s vaccine contained a weakened live virus, it could be re-activated by passing through the gut, causing occasional cases of polio and paralysis. Paul Offit, MD, notable vaccine advocate and immunologist, concludes in his book on the incident that “by creating the perception among scientists and the public that Salk’s vaccine was dangerous [it] led in part to the development of a polio vaccine that was more dangerous.” And, it did lead to the effective regulations that we enjoy today that give vaccines a safety record “unmatched by any other medical product.” Dr. Bellanti takes some issue with this conclusion and credits both Drs. Salk and Sabin with their monumental contributions to the conquest of poliomyelitis and suggests the global end to polio transmission would have been inconceivable without both the “killed” (Salk) and “live” (Sabin) vaccines.

It’s fascinating how over the course of our history, these “giants” of medicine crossed paths with the College. Our history is incredibly rich, and we’ve always worked to bring important thought leaders in the field to our members at our Annual Meetings. It’s something we are proud to continue today as we create a strong future.

Many thanks to former College Historian Dr. Joseph A. Bellanti, for his editorial assistance in the preparation of this article.

Got a great memory of College leaders or past allergy and asthma treatments? Share it with us!

References:

- Allen, Arthur. “Vaccine: The Controversial Story of Medicine’s Greatest Lifesaver.” Google Books. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 May 2017.

- “The Death of a Disease: A History of the Eradication of Poliomyelitis.” Google Books. Ed. Bernard Seytre and Mary Shaffer. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 May 2017.

- Fitzpatrick, Michael. “The Cutter Incident: How America’s First Polio Vaccine Led to a Growing Vaccine Crisis.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. The Royal Society of Medicine, Mar. 2006. Web. 17 May 2017.

- Haelle, Tara. “Polio Vaccine Found “Safe And Effective” 60 Years Ago: What Would Salk Think Today?” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 01 June 2015. Web. 17 May 2017.

- Klein, Christopher. “8 Things You May Not Know About Jonas Salk and the Polio Vaccine.” History.com. 28 Oct. 2014. Web. 17 May 2017.

- Matysiak, Angela. “The Myth of Jonas Salk.” MIT Technology Review. MIT Technology Review, 30 Dec. 2013. Web. 17 May 2017.

- McDonald, Sharon. “Science and the Regulation of Biological Products.” (2002): Sept. 2002. Web. 16 May 2017.

- Offit, Paul. “The Cutter Incident.” Google Books. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 May 2017.

- “Timeline.” Timeline | History of Vaccines. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, n.d. Web. 17 May 2017

- “Vaccine Safety.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28 Aug. 2015. Web. 17 May 2017.

- Russell, Sabin. “When Polio Vaccine Backfired / Tainted Batches Killed 10 and Paralyzed 164.” SFGate. N.p., 25 Apr. 2005. Web. 17 May 2017.