Since the College began, there have been a lot of changes in the way we treat allergies and asthma. “When Benadryl hit the market in 1946, many assumed it would mean the end of the specialty,” said Joseph Bellanti, MD, FACAAI, College historian and past president. However, science and research advanced, and even better treatments for allergies and asthma were discovered – and the specialty continues pushing forward into the future. Embracing our rich history gives us the opportunity to build on where we came from, and helps us to create a stronger future for allergists everywhere.

When the College was founded by Frederick Wittich, MD, in 1942, allergy was barely a distinct specialty. There wasn’t a way for practicing allergists to be certified, and many physicians dabbled in treating these conditions. The College was created so members could gather and share scientific ideas to advance the field and to protect patients. Dr. Wittich is best known for his studies of allergic disease in animals, and was the first person to show that dogs have allergies, too. Because of his involvement with animals and allergy, the first Annual Scientific Meeting of the College, held in Chicago in 1944, featured a whole veterinary section on allergy and immunology. Meeting attendees hoped that by studying how allergy works in animals, they could better understand how it works in humans.

A nd although 1942 doesn’t sound like that long ago, allergy treatment looked very different than it does today! Those were the days when Benzedrine inhalers were still freely available (a potent amphetamine inhaler – often supplied to troops in World War II – was frequently abused). Antihistamines hadn’t even been dreamed up yet, Benadryl first came to the market a few years later, and members of the allergy community were worried the new drug meant the end of their specialty. Would there be a need for immunotherapy if the disease could be treated with a simple antihistamine pill?

nd although 1942 doesn’t sound like that long ago, allergy treatment looked very different than it does today! Those were the days when Benzedrine inhalers were still freely available (a potent amphetamine inhaler – often supplied to troops in World War II – was frequently abused). Antihistamines hadn’t even been dreamed up yet, Benadryl first came to the market a few years later, and members of the allergy community were worried the new drug meant the end of their specialty. Would there be a need for immunotherapy if the disease could be treated with a simple antihistamine pill?

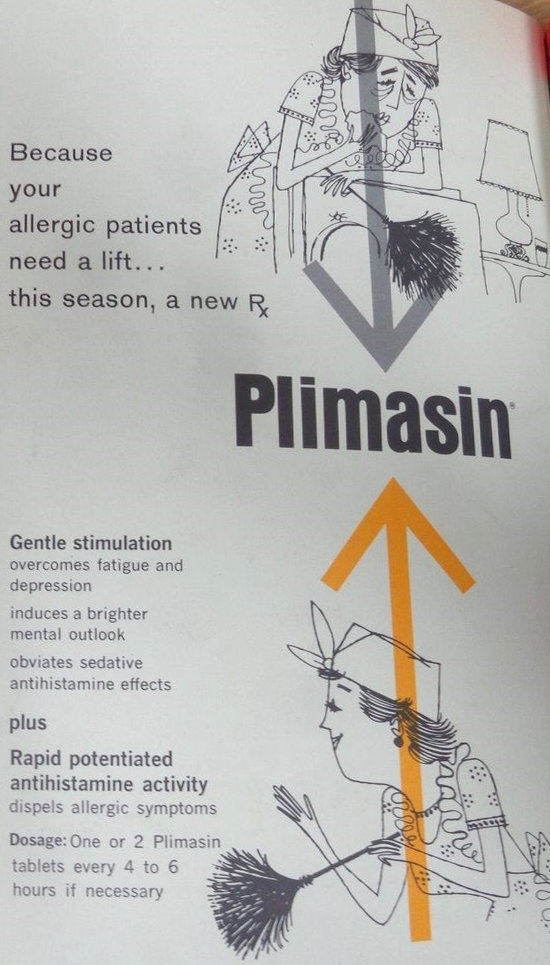

Part of the reason for creating the College was to establish a place where ideas and research could be shared, both at the Annual Scientific Meeting and in Annals. As scientific research advanced, so too did the treatment of allergies and asthma. New breakthroughs meant that allergists were no longer just prescribing things like Plimasin (an antihistamine combined with Ritalin to offset sedation) for allergies. Asthma treatment advanced beyond simply treating attacks with subcutaneous epinephrine and a dose of Susphrine. Steroids like Medrol first came on the market in the 1950’s, and opened a new door for treating asthma and allergies. Although not often used anymore because of side effects, they did pave the way for modern, inhalable steroids.

IgE was simultaneously discovered in the late 1960s by two independent groups, Kimishige Ishizaka et al and Hans Bennich and Gunnar Johansson. “The technologic applications of this discovery continue to occur and have led to better diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for the patient with allergy,” wrote Dr. Bellanti in a 1993 Annals article titled “Proud of the past: planning for the future.”

Over at the College, leaders like Lowell Henderson, MD, FACAAI, addressed issues like burnout. His prescription to cure “running out of steam for those reaching mid-career” was for practicing allergists to become investigators and participate in research. “This gives freshness and interest to your life, keeps the intellect active, benefits those who apply to you for advice, and enriches your profession,” said Dr. Henderson in his presidential address at the Annual Meeting. This attitude is what helped push advancements in allergy and asthma treatments.

Over at the College, leaders like Lowell Henderson, MD, FACAAI, addressed issues like burnout. His prescription to cure “running out of steam for those reaching mid-career” was for practicing allergists to become investigators and participate in research. “This gives freshness and interest to your life, keeps the intellect active, benefits those who apply to you for advice, and enriches your profession,” said Dr. Henderson in his presidential address at the Annual Meeting. This attitude is what helped push advancements in allergy and asthma treatments.

Finally, in 1972 after a 30-year-long wait, one of the founding goals of the College was accomplished – the American Board of Allergy and Immunology (ABAI) was established. The first certifying exam was given in 1974 – College members finally had a distinct, certified specialty. Around this same time, the Joint Council of Allergy and Immunology (JCAAI…now the College’s Advocacy Council) was formed in response to a changing socioeconomic climate.

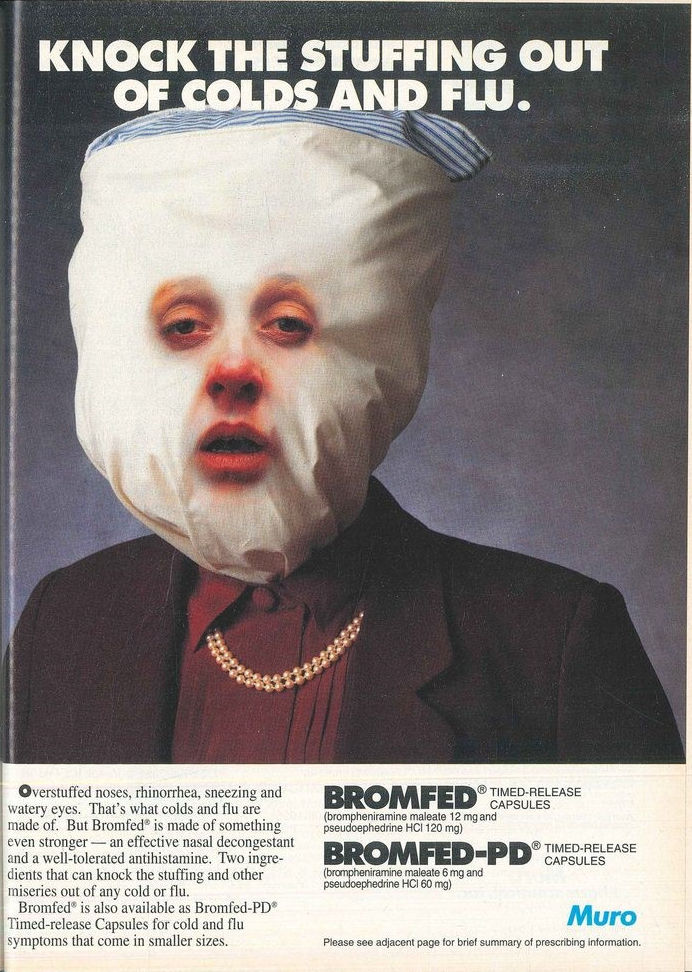

Second-generation antihistamines (such as loratadine and cetirizine) appeared in the early 1980s, favored by allergists and liked by patients for the lack of sedative side effects. Third-generation antihistamines like fexofenadine came to market in the mid-90s. Just when it seemed like the specialty was safe, in the early 2000s these drugs began to move from prescription-only to over-the-counter (OTC). Additionally, ephedrine drugs (and later, pseudoephedrine) offered quick relief from congestion and asthma. Now anyone could treat their allergies and asthma themselves just by walking into a corner drug store – creating the possibility that people who most needed the help of an allergist weren’t getting it. Plus, costs for these medications went up, since insurers don’t cover OTC treatments. It was Benadryl all over again.

Meanwhile, at the College during the early 1980s, Gilbert Barkin, MD, FACAAI, decided to shake things up to recruit more members – especially younger ones. The executive offices were moved from Boulder to Chicago, and a new editor was selected for Annals. A strategic plan was put in place, and the College witnessed “an unprecedented growth in membership and financial stability,” wrote Dr. Bellanti. In 1987, the College merged with the American Association of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, and our named changed from the American College of Allergists to the American College of Allergy and Immunology (ACAI). Two Annual Meetings were held that year – one in Las Vegas and one in Boston – where sessions emphasized the need for allergists and other organizations to work together to help the specialty move into the future.

Meanwhile, at the College during the early 1980s, Gilbert Barkin, MD, FACAAI, decided to shake things up to recruit more members – especially younger ones. The executive offices were moved from Boulder to Chicago, and a new editor was selected for Annals. A strategic plan was put in place, and the College witnessed “an unprecedented growth in membership and financial stability,” wrote Dr. Bellanti. In 1987, the College merged with the American Association of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, and our named changed from the American College of Allergists to the American College of Allergy and Immunology (ACAI). Two Annual Meetings were held that year – one in Las Vegas and one in Boston – where sessions emphasized the need for allergists and other organizations to work together to help the specialty move into the future.

Diane Schuller, MD, FACAAI, was the College’s first woman president in 1994. Under her leadership, our name changed again to include the word “asthma” – an effort to create awareness that allergists are the leading experts in treating this condition. A lot of work was put into situating allergists as the primary professionals for treating allergies and asthma. By the time the new millennium rolled around, Emil Bardana, MD, FACAAI, was hard at work expanding the College’s presence internationally – and he created the valuable publication, AllergyWatch.

As the years went on, research and science marched forward, and the latest treatments and ideas continued to be shared at the College’s Annual Meetings. A deepening knowledge about asthma led to the first biologics appearing around 2014 in the United States. While there are more OTC treatments than ever before, allergists today have these personalized treatments in their toolbox to help patients. Allergists are now able to create treatment plans that are directed toward precision medicine. And the College is here to be a resource for patients so they can understand their condition and find an allergist who can offer real relief.

It’s great to see how far we’ve come in treating allergies and asthma. While there were some bumps in the road where the specialty seemed “doomed”, it’s always pulled through. Allergists have always been there to offer the best treatments for patients – the type they can’t get OTC. The future of allergy looks strong and bright. The College has always offered a place where members can exchange ideas and soak up education on the latest treatments, and patients can find information or an allergist. It’s been 75 years and we’re stronger than ever – and are feeling excited about what the future of allergy and asthma will look like.